|

| Image ©Vince Garcia |

At Christmas, differences between ourselves and our

elderly relatives can be shoved into garish spotlight – our backgrounds; our

upbringings; our educations; our politics and social outlooks; our attitudes

towards religion, ‘authority’, life and death, money, health, gender issues,

race, tradition, relationships; and so on. Note that one difference I have not

mentioned in the list is age; I have not mentioned it, because it is not, per se, a relevant difference.

Enlightened views clash with entrenched prejudices. Modern

flexibility slumps uncomfortably in its dining-chair beside stiff-backed

‘Victorian values’ of ‘work ethic’, ‘sense of duty’, belief in all-powerful

deity, distrust of things ‘foreign’. Bitten tongue and knotted stomach conspire

to block the passage of dry turkey, until copious wine comes to the rescue.

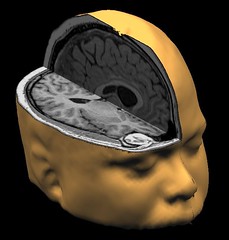

Aging is a wonderful thing. A life spent learning, open to

new experiences, experimenting, thinking, laughing, loving, and caring will

create a vibrant mind of untold complexity. The problem with it – as we are all

too aware – is that it tears at the mind and body. As the brain falls prey to

structure-wrecking illness, such as Alzheimer’s, the mind begins to wander and

fade. Impoverished by the ailing body, sensory input to the brain stutters. And

when that happens, we the cognitively intact must confront the threadbare

consciousnesses of our ailing relatives. To a large extent, what remains is

governed by what went before; a flexible, optimistic mind may well outlast an

entrenched one. Neurons well ‘attuned’ to making new connections may find ways

to circumvent some of the damage as it progresses. The mental macrocosm

inhabited by the sufferer will certainly shrink, so it pays to have a lot of

cognitive ‘reality estate’ to spare.

So to the thought experiment: What if the capabilities of

the brain and body were not looted by aging? What new, lucent complexity

would those time-honed minds begin to exhibit? As we have no experience of such

persons, this is difficult to answer. Nevertheless, it may be easier to imagine

loving, vibrant elderly people developing into super-wise ancients than to

imagine the curmudgeons doing so. Stuck in the past and embittered by long-held

prejudices, the curmudgeon’s limited macrocosm has reduced to a dot. But what

if we had time to shore it up, stretch out its walls, and fill it with

enlightened wonder?

Some of us are slow starters. For some, enlightenment

takes only time; for others, it takes therapy, drugs, or neurosurgery. In a

world without aging, very long-lived individuals would be expected to play a

full part in society; ‘old age’ would no longer be an excuse for fixed,

discriminatory attitudes. Though some brains may be ‘wired’ for prejudice and

dysphoria, society would need to find humane ways to mitigate this. However, I

think that the chance to begin again as rejuvenated, valued citizens would, in

most cases, be enough to bring about epiphany.

If we find ourselves struggling with our elderly relatives

this Christmas, we could perhaps try to bear this in mind. When tempers fray

and boundaries are crossed, when stereotyping rears its ugly head, when disdain

sours the fragrant atmosphere, when nothing we do is thought well of; we could

try to bear in mind not what they once were, but what they could – given

a new chance at life and a heady draught of wonder – become.