Following on from my recent

article Neuro with

Everything, where I raised the vexatious issue of

so-called neuropolitics, I will now take a deeper refractory look at our

psychological blocks against things constitutional. Why are we uncomfortable

about the mechanics of nationhood? Because we don’t really know what ‘nations’

are. Why is this relevant? Because, in Scotland , we are in a process of

building a new one. Now, pass me that torque wrench.

Nations (yawn), how un-futuristic.

Not so fast, there. While futurists tend to look forward to a time when all

humankind will live in harmony, perhaps even under the auspices of a benevolent

form of world government, some of us ponder what is the most expedient way to

get there. Nations can be desperately un-futuristic, especially when they are

cobbled together from the zombie vestiges of dead empires. Alternatively, they

can be dynamic, paradigm-shifting agents in this world of exploding complexity.

Nations don’t exist. Countries

don’t exist. Landmasses do exist, at least in the ordinary physical sense.

People exist, living on landmasses. No, that’s not right. Roving biomasses

exist on landmasses. Better. Some of these roving biological entities (us) are

self-aware. These self-aware entities tend to group together with others whom

they feel are like them – they are social entities. This can cause problems.

These entities tend to argue with, fight with, and sometimes kill others whom

they feel are dissimilar to them. Nations form. ‘In-groups’ delineate their

territories using convenient geological boundaries, and then call these

nation/territory constructs ‘countries’.

The term statist is often

used as an insult, these days, against people who think that nation states can

be effective vehicles for delivering on the needs and aspirations of

individuals. You might expect such an attitude from capitalists (even the

modern anarcho-capitalist variety) and ‘libertarians’, but why do many

technoprogressive leftists also take this stance? I think it is because they

assume that all nations, both existing and emerging, have been and will be

built using the same failed templates that past nations used.

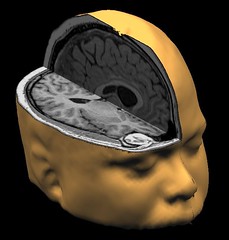

People are ‘agents’

within nations; neurons can be thought of as ‘agents’ within persons. Yet, perhaps because nations

are seen as ‘not natural’ and ‘manufactured’ whereas persons are seen as wholly

natural, we tend to dismiss the fact that they are both types of abstraction.[i] There are many ways in which neurons in their communicative context of human

brains are different from humans in their communicative context of nations; I

am not claiming that they produce the same types of abstraction, only that both

can be seen as abstraction-generating agents of sorts.

Nations may behave unpredictably, but they each seem to have a unique ‘character’. They can be calm or aggressive, colourful or dour, outgoing or reclusive. They may form intimate relationships with other nations. Sometimes those relationships become strained, or abusively one-sided.

We represent ourselves in myriad

different ways. We change ourselves. We think. We act. Those of us who spend

time pondering the future of the human race should not pretend that we can leap

from here to utopia in a single bound. The Singularity might happen, but, then

again, it might not. We need to interrogate our world, and engage with it. We

cannot sit around waiting for some kind of ‘hard takeoff’.[ii]

The elevation of morality is

important to me. I want to live in a morally-elevated world. On this

trajectory, I choose the expedient of personal agency; I also find that I must

choose the expedient of the fair, diverse, creative, forward-looking,

independent nation state that I think we have an opportunity to create here.

This may be unfashionable in futurist circles, but what should a futurist care

for fashion?

Empires – and bloated nations

that act like empires – shrink persons. They reduce us to mere ‘subjects’ with

little more agency than synaptically-weak neurons in a conflicted brain. But

consensual nations, chosen freely and fairly, can connect us together in

fascinatingly teleodynamic ways. They can bring us together and help us to

reach out. They can give us a clear voice in the growing din. Under the right

circumstances, they can grant us citizenship within a well-adjusted,

constantly-questioning, fully-functioning, enlightened ‘national consciousness’.

[i] D. Parfit. Reasons and Persons. Oxford :

Oxford University

[ii] Inspired by a talk, in 2013, by James Hughes Ph.D., of the

Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies